Executive Summary

Many essential consumer goods, from life-saving chemotherapy drugs to the fragrances and flavors in everyday products, come from compounds found in plants. These are cornerstones of multi-billion dollar markets where consumer demand for sustainable, natural products is growing at an unprecedented rate.

However, the methods used to acquire them are often anything but sustainable. The development of more sustainable approaches, such as Microbial Cell Factories, presents complex engineering challenges, leading to costly and slow R&D. Active Learning can revolutionize the traditional research cycle by delivering a faster, cheaper and more intelligent R&D process, paving the way for a sustainable future.

Tackling a Multi-Billion Dollar Sustainability Challenge

The global economy relies heavily on plant-derived compounds, yet our methods for sourcing them are pushing ecological limits. Current production methods mainly use chemical extraction from plants. These methods harm the environment and cost a lot (Bisht et al., 2025). They cause land damage and produce many greenhouse gas emissions (Barjoveanu et al., 2020). This reliance on traditional agriculture and extraction creates unstable supply chains and high costs. It also causes a large environmental impact. Recent analyses of natural-ingredient markets (Roland Berger, 2025) show that this situation is no longer sustainable.

The future of sustainable production lies not in crop fields, but in bioreactors containing "Microbial Cell Factories" (MCFs). These are microbes genetically engineered to produce high-value compounds efficiently. However, the path from concept to reality is fraught with complexity. Moving metabolic pathways from plants into microbes is incredibly complex. Engineers must optimize many parts, including enzyme molecules, cell metabolic networks, and industrial bioprocesses. This multi-scale optimization challenge has historically been a bottleneck, slowing down innovation and keeping sustainable alternatives out of reach.

This is precisely where Artificial Intelligence comes in. ML6 is at the forefront of this change with deCYPher, a Horizon Europe project that leverages Active Learning to create these MCFs more efficiently than ever before. It reflects the broader evolution happening across synthetic biology, where active learning strategies and deep learning methods are increasingly essential to accelerate discovery. The real-world impact of this intelligent approach is a new paradigm for scientific discovery, delivering three significant advantages over the traditional research cycle:

- Speed: Greatly shortening research and development cycles.

- Cost Reduction: Minimizing expensive and time-consuming lab experiments by focusing resources on the most promising designs.

- Risk Mitigation: Eliminating unpromising avenues early in the process, ensuring resources are invested for maximal impact.

The Challenge: Navigating Infinite Biological Complexity

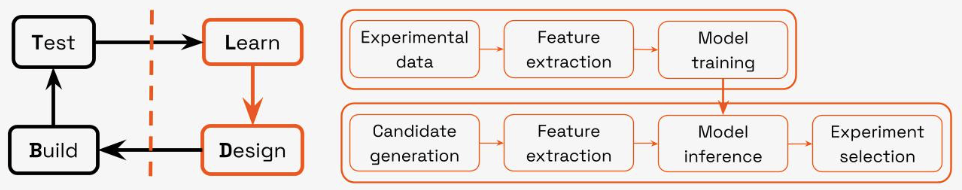

The foundational framework used to engineer synthetic biological systems is the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle: an iterative process of designing a biological construct, building it, testing its functionality and learning from the results to further refine the design, thereby converging towards an optimized solution with each cycle.

In recent years, advances in technologies such as DNA synthesis and sequencing technologies have accelerated the 'Build' and 'Test' steps of this cycle. Yet, the 'Design' and 'Learn' stages remain significant hurdles. The design space for even a single protein is so vast that it exceeds the number of atoms in the universe, which makes intuition, brute-force screening, and traditional decision-making ineffective. This raises two fundamental questions: How do we intelligently choose which experiments to run from a near-infinite list of possibilities? And how do we ensure we extract maximum value from every single experiment to guide the next round of design? This is where traditional methods fall short. Instead of relying on intuition or brute-force screening, Active Learning provides a data-driven method to guide researchers toward the most promising designs.

Our Solution: An AI Co-Pilot for Smarter Scientific Discovery

Our role in the deCYPher project is to deliver an AI-powered platform that transforms the DBTL cycle from a slow, manual process into a rapid, intelligent, and automated workflow. The core engine can be applied to any optimization problem, and we equip it with specialized tools to optimally handle specific use cases at the protein, metabolic, and industrial process levels.

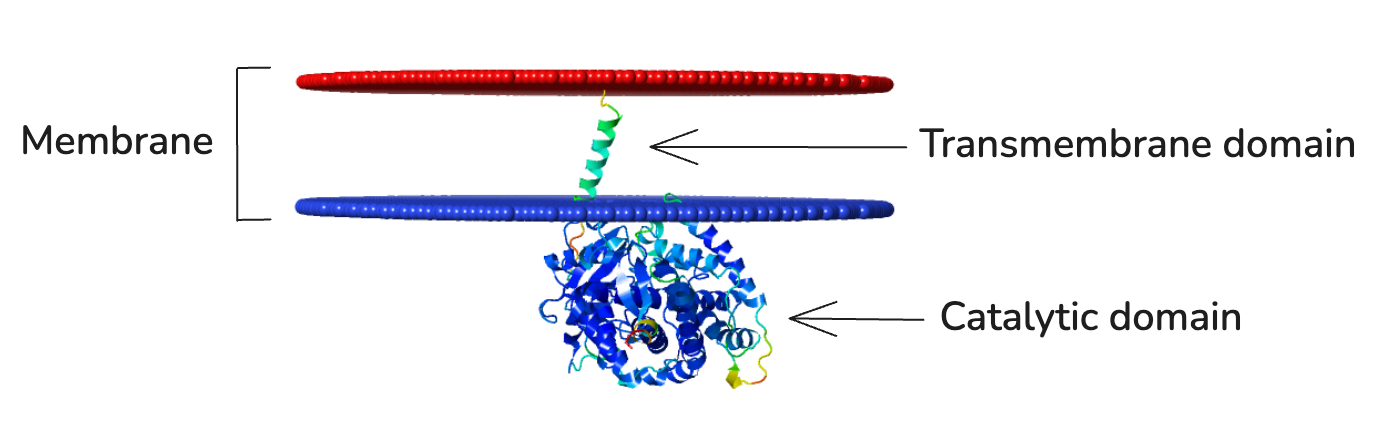

3D model of a membrane-inserted CYP enzyme (made using AlphaFold and PPM).

The project focuses on plant Cytochromes P450 (CYPs), an exceptionally valuable but notoriously difficult enzyme family to work with. To illustrate our solution, consider the challenge of engineering a CYP's transmembrane domain (TMD). This problem comes from a basic biological mismatch. In plant cells, the enzyme attaches to a specific membrane called the endoplasmic reticulum. But microbial cells are simpler and do not have an endoplasmic reticulum. For the enzyme to function in an MCF, its anchor must be redesigned, a classic and complex protein engineering task perfectly suited for an AI co-pilot.

Detailed view of the AI-driven “Learn” and “Design” phases of the DBTL cycle.

Step 1: Teaching the AI to Understand Biology

The AI-driven process begins when experimental data from the initial Test phase is used to automate the Learn stage. A crucial step here is our Feature Extraction module, which translates raw amino acid sequences (the primary representation of proteins) into a rich numerical language that a machine learning model can understand. As we covered in a recent post, this extensive feature extraction from protein sequences is one of the key ways AI tools are supercharging the decades-long quest to harness proteins.

For TMD engineering, you can calculate and leverage embeddings from protein language models like ESM. You can also use structure-derived features from 3D models predicted by tools like AlphaFold. Another option is to use simpler compositional features from libraries such as Biopython. These features can be further refined via tailored feature selection workflows to become the input to optimally train regression or classification models.

Importantly, this is not a one-size-fits-all process; depending on the specific use case, we can design and experiment with different feature extraction workflows. Once calculated, this comprehensive feature set is then used for Model Training, creating a model that can discern the complex patterns connecting a TMD's properties to its experimental success.

Step 2: Generating a Universe of Possibilities

Once trained, this predictive model becomes the engine for an automated Design phase. The first step here is handled by our Experiment Generation module, a versatile toolkit of different generative approaches which can be used independently or combined together into custom workflows depending on the engineering goal. We can for instance use ProLLaMA to generate sequences from the TMD and CYP protein superfamilies, and feed successful sequences into ESM's masked language modeling to create a library of variants around them. This allows us to combine broad, family-level exploration with fine-tuned local optimization. To broaden this further and allow us to explore solution spaces beyond natural protein families and their variants of parent sequences, we can also use inverse folding models like ProteinMPNN to predict the most likely sequence of a target protein structure, which can itself be generated from a structure scaffold using a diffusion model like RFDiffusion. Combining these different approaches allows us to produce a large and diverse pool of relevant candidate experiments that provides the raw material for our active learning pipeline to select from.

Step 3: Selecting the Smartest Experiments with Active LearningEach generated candidate undergoes the same feature extraction as the experimental data, after which the trained model can predict two key outputs for these candidates: the likely experimental outcome and a corresponding certainty score. This dual output is the key to the final step: Experiment Selection. This is where our Active Learning strategy comes into play. Instead of simply picking the candidates predicted to be successful, it balances the trade-off between exploitation (choosing designs likely to work) and exploration (choosing designs the model is unsure about, to learn faster). The result is a small, optimized set of ranked candidates that represents the most strategic choices for the next round of lab experiments.

This is also where the pipeline acts as a co-pilot, designed to augment, not replace, the human expert. The AI provides data-driven recommendations, but the final selection benefits from the experience and intuition of the scientific teams. By feeding these carefully chosen designs into the next Build and Test cycle, we ensure our model becomes more accurate with each iteration, significantly accelerating the discovery process.

More Than a Single Solution: A Platform for Future Innovation

The most significant advantage of building such a robust pipeline is that it's not limited to a single use case. This is possible because the platform was designed not as a rigid pipeline, but as a smart "co-pilot" for the scientist. At its heart is an active learning engine, which can be equipped with different datasets, generative methods and analytical tools to optimally train models for specific use cases.

Now, with this foundational work on protein engineering, we can apply the same framework to the project's next stages. This modularity is what unlocks the platform's true potential. By simply swapping the data inputs and tools, the same engine that optimizes enzymes can be pointed at entirely new challenges across the life sciences. For instance, it could be combined with multi-agent setups for steering patient treatment, or genomic selection and vision AI methods for advanced precision agriculture. This is the essence of our approach: building not just one-off solutions, but powerful, adaptable platforms that can accelerate innovation across the entire landscape of Life Sciences.

Conclusion: A New Paradigm for Biological R&D

The protein design space is one of the most exciting frontiers in technology, representing a massive leap forward in our ability to partner with biology. For the first time, we are moving beyond decoding biology and beginning to reshape it. We can design enzymes from scratch, rewrite metabolic pathways and create biological systems that never existed before. Each new discovery brings us closer to true "protein fluency": the ability to read, write, and edit the language of life itself.

deCYPher represents this vision in its purest form. By uniting advanced machine learning with modern biotechnology, it opens a sustainable path for innovation. It accelerates discovery, reduces environmental burden and empowers researchers to tackle the challenges that matter most. It signals a future where AI does not simply analyze biology but works alongside it, transforming synthetic biology, active learning, and protein design into engines for a more sustainable world.